In the late 1960s nothing was hotter in Northern England than American rhythm & blues music. People would take speed and go out to all night dance parties where they’d dance to The Four Tops and Wilson Pickett until dawn. At the beginning of the 70s the sound of American r&b was changing, and the kids in Liverpool weren’t hip to the new sound. They wanted more “Ain’t No Mountain High Enough” and were being given “What’s Going On”. To feed the demand for new songs that fit the 60s soul sound, DJs began combing through back catalogs of lesser known and regional American r&b labels, hoping to find songs that would scratch the “new music” itch but would also be familiar enough that the kids would dance to it, creating a strange new strata of music: songs that had been released years ago and were forgotten in Detroit and Memphis but were now regional hits in Manchester and Wigan. These songs became known as “Northern Soul” and turned also-ran songs like “Nothing Can Stop Me” by Gene Chandler and “Landslide” by Tony Clarke into chart juggernauts (assuming the chart was based in Leeds). Probably the most well known Northern Soul track is Gloria Smith’s “Tainted Love”, later covered by Yorkshire synthpop duo Soft Cell.

On a certain level, this entire yearlong project is an attempt to do what crate-digging Sheffield DJs were doing in the 1970s. The powers that be aren’t making the same kind of mid budget tentpoles that I’m interested in seeing, so I’m mining the past to see if there are any forgotten relics that were lesser known in their time but can now be seen as bangers that we just didn’t appreciate at time of release. Unfortunately movies don’t really work on the same business model as music, and so it’s substantially rarer to find something that was made with some clear production values behind it but was also undermarketed and underappreciated. That rarity though just makes it all the better when you find something that is an absolute gem of a blockbuster-that-never-was, something like Sunshine.

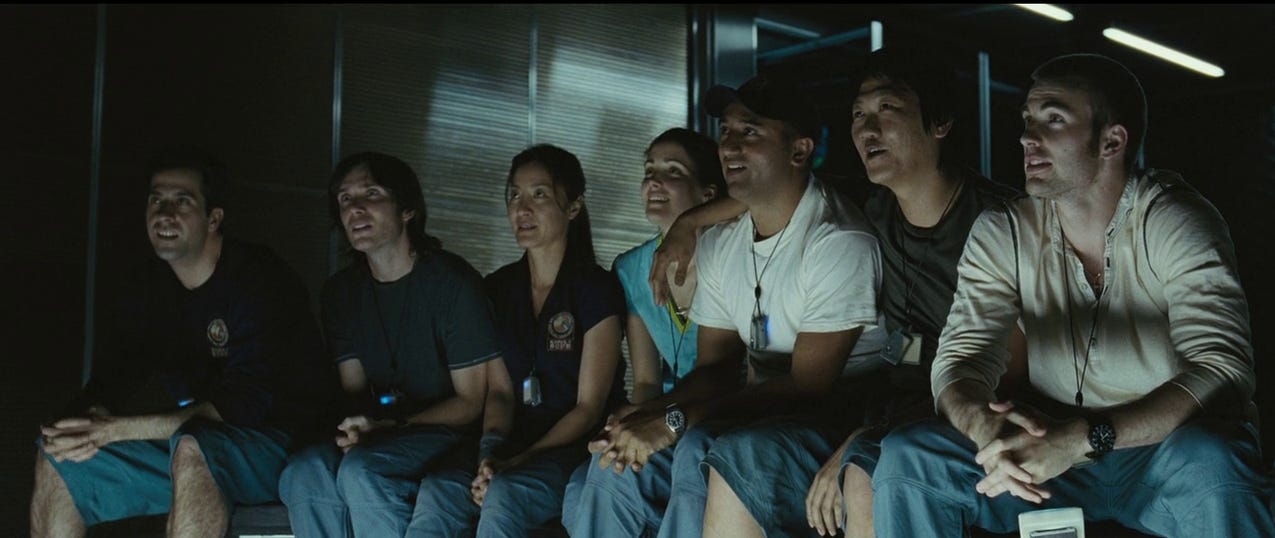

Sunshine is the second collaboration between screenwriter Alex Garland, director Danny Boyle, and star Cillian Murphy1 after the smash critical and commercial success that was 28 Days Later (2002). It is the story of the Icarus II, a spaceship in 2057 sent to the sun with a nuclear payload the size of Manhattan. Its mission is to create a new fusion chain reaction and create a “star within a star” due to the sun unexpectedly starting to die years prior. The crew consists of captain Kaneda (Hiroyuki Sanada), communications officer Harvey (Troy Garity), navigator Trey (Benedict Wong), pilot Cassie (Rose Byrne), engineer Mace (Chris Evans), as well as a physicist named Capa (Cillian Murphy) charged with ensuring that the nuclear payload is delivered and explodes properly, a botanist named Corazon (Michelle Yeoh) who tends the ship’s “oxygen garden” that keeps the crew alive, and a doctor and psychologist named Seale (Cliff Curtis) to make sure everyone stays physically and mentally healthy. As happens in just about every movie set in space that isn’t a Star Trek or Star Wars property, things start going wrong and people start having a very bad time. Unlike most space-mission movies however, the consequences of The Icarus’s mission failing isn’t that the crew dies, it’s that humanity dies, upping the stakes substantially.

Alex Garland’s film career has largely focussed on treading well worn aspects of speculative fiction (zombies, robots, spacemen, etc) but putting a novel twist on them (what if the zombies… fast?). Much like Aaron Sorkin, I feel like Garland has good ideas and is capable of creating interesting stories, but that those stories are best experienced when putting them through the lens of a seasoned director, and Danny Boyle understands how to tell an Alex Garland story. The two 28 [Time Period] Later films that Boyle has directed and Garland has written put front and center the really interesting parts of a zombie-based civilizational collapse (namely: the ways in which English culture reasserts itself even in the face of apocalypse, and what gets left by the wayside), and don’t focus on the aspects that are a little less compelling (like the fact that the genesis of the rage virus is that scientists showed a monkey the news until it got so mad it became a zombie). Sunshine is no different, in that it takes a standard sci-fi story (something terrible is happening in space) and applies just enough of a twist on that formula to make it interesting (the bad thing is happening on and around the Sun), but Boyle keeps the focus on the characters, their human interactions, and the dire stakes they’re dealing with, keeping the story from spinning off into hacky college-dorm-bong-rip-directions.

The power of Sunshine comes from the dichotomy between two facts about the sun. First: the sun is the source of all energy on Earth, and we literally owe our lives to its existence, and second: the Sun is such an unimaginably powerful source of energy that human beings interacting directly with it is not unlike a gnat interacting with an atom bomb. While the plot of Sunshine revolves around a dying sun, a dying sun is still unfathomably powerful and will kill you dead if you slip up for even a second. The Icarus II mission in Sunshine lasts for three years. Imagine not slipping up even once for three years. Naturally, someone does, and the terrifying events of the film immediately follow from that. We need the sun to survive, but it will also destroy your tiny little spaceship if you angle the pitch of your deflector shield by even 1.1° off.

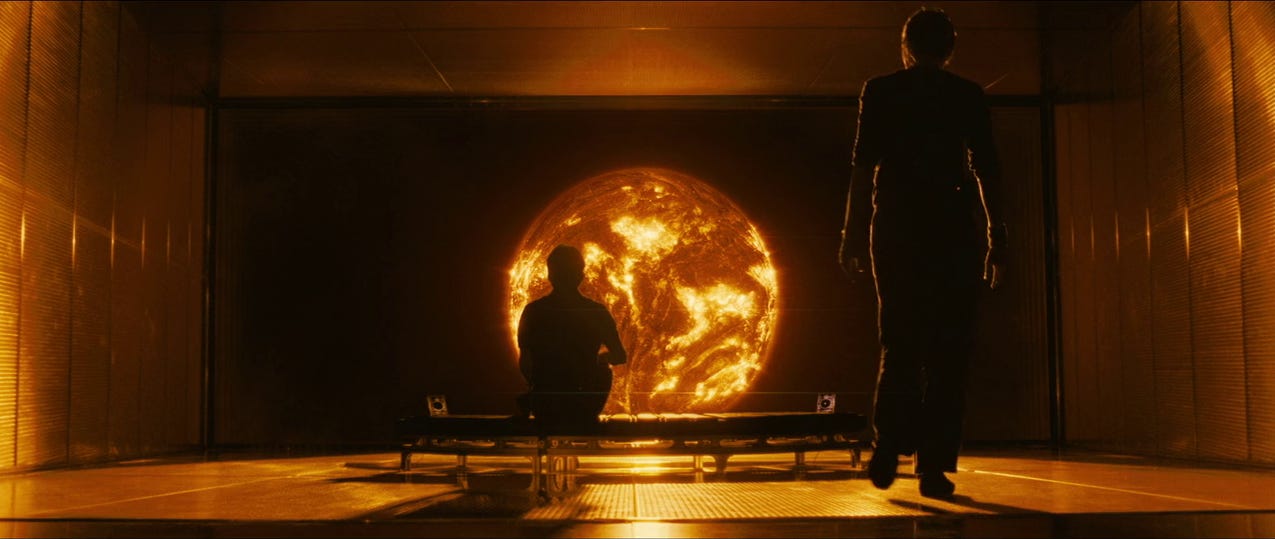

The film opens with Dr. Searle sitting in the observation deck of the ship looking at a dimmed image of the Sun, filling his field of vision. He asks the onboard computer if it can raise the dimness of the shades from 2% to 4%. The computer demures, informing him that that level of brightness would blind him. He eventually talks it into 3.1% for 30 seconds, which causes the room to fill with sunlight so intense that he reacts as though he were having a religious experience. When I was younger I didn’t think about how the sun affected my mood much. Living in the sweet, sunny south, the sun was just kinda always there. At the age of 30 I moved to Minnesota, where I knew the winters would be cold, but what I wasn’t prepared for was how dark they would be. The northern latitude causes extreme shifts in daylight availability through the year. By Christmastime if you work in a windowless office (as I do sometimes) it’s possible to go through your day never experiencing the sunlight, commuting to work and home in the darkness. By contrast, the summers are bright and intense. I’ll never forget the strange feeling I felt when I saw a movie that started at 7:00 PM in late June shortly after moving and exiting the theater to find it was still sunny out. Suddenly I understood why Prince’s definition of paradise in “Let’s Go Crazy” was “You can always see the sun, day or night”. The sun can feel a bit like a drug, and Sunshine as a film asks “what happens if you OD on sunlight?”

In the final act of Sunshine, after the crew and the ship have been decimated by a combination of human error and the unknowable power of the sun, a final impediment to the Icarus II’s mission arrives in the form of a man named Pinbacker (Mark Strong), the commander of the failed first Icarus mission to reignite the sun. What we come to realize is that the first Icarus mission failed because Pinbacker lost his mind due to a kind of religious mania brought on by proximity to the sun, insisting that he has newly acquired divine knowledge that it is God’s will that humanity should perish. Due to his newfound sun cult zealotry he attempts to thwart the Icarus II’s crew through murder and sabotage. Many viewers of Sunshine were turned off by this swerve from the film’s opening as a space-disaster film into slasher-horror. Quentin Tarantino said that the film’s final act was “far beyond disappointing”. Roger Ebert said that the “drummed up suspense at the end is non-essential”. I would counter these remarks with “you do not know how to watch this movie”.

Pinbacker as the final obstacle to the Icarus II’s mission simply represents another way in which the power of the sun is manifesting danger to her crew. Just as much as the beam of light that starts a fire in the ship’s oxygen garden, Pinbacker represents the power of the sun hitting in a destructive way, it’s simply that the origin of this danger is psychological rather than physical. The sun has a powerful effect on the human psyche. Some of the earliest examples of human religion are sun cults, including the worship of Ra in ancient Egypt and the worship of Huitzilopochtli in the Aztec empire, both primary deities in their respective pantheons. People experiencing the power of the sun 150 million kilometers away can develop parasocial relationships with the sun, ascribing it motivations and desiring to appease its mighty power (sometimes even with human sacrifices). Imagine what effect it can have when practically on its doorstep.

It’s important to remember as well that highly destructive human actors can be just as detrimental to life-and-death situations as engineering problems are. As I write these words theocrats the world over seem to be hell bent on either letting the world burn due to climate change or actively blowing it up to spite their enemies. To pretend that we need not consider human obstacles to natural problems is naive at best. Pinbacker is no hare-brained excuse for some extra third act suspense, he represents just another aspect of the sun’s power lashing out at the Icarus II’s crew.

Beyond the excellent sci-fi story that Sunshine is telling it simply exists as a magnificent example of filmcraft. The cast is a murderer’s row of talent. In a world where Oppenheimer (2023), Everything Everywhere All At Once (2022), Materialists (2025) and Shōgun (2024) exist you do not need me to tell you that Cillian Murphy, Michelle Yeoh, Chris Evans, and Hiroyuki Sanada are positively magnetic onscreen. The art direction and production designs are top notch and make the Icarus II feel like a real place and renders its exteriors the most terrifying place imaginable. The special effects are gorgeous, and were purchased for a song compared to other big films of its era (Sunshine’s budget is less than a third of Fantastic Four: Rise of the Silver Surfer, has a comparable amount of effects shots, and unlike FF does not look like absolute garbage) due to the absolutely shocking decision by producer Andrew McDonald to give the special effects team ample time to produce their work. Turns out if you don’t try to actively bankrupt an effects house they do good work for you. Who knew?

I have little hope that my little film blog will be the thing that propels Sunshine to cult favorite status, but honestly its day of vindication is coming. I urge you to watch it, and in a few years time when there are 25th anniversary screenings reclaiming its legacy you can say you got on board before everyone else did.

Rating: ★★★★★

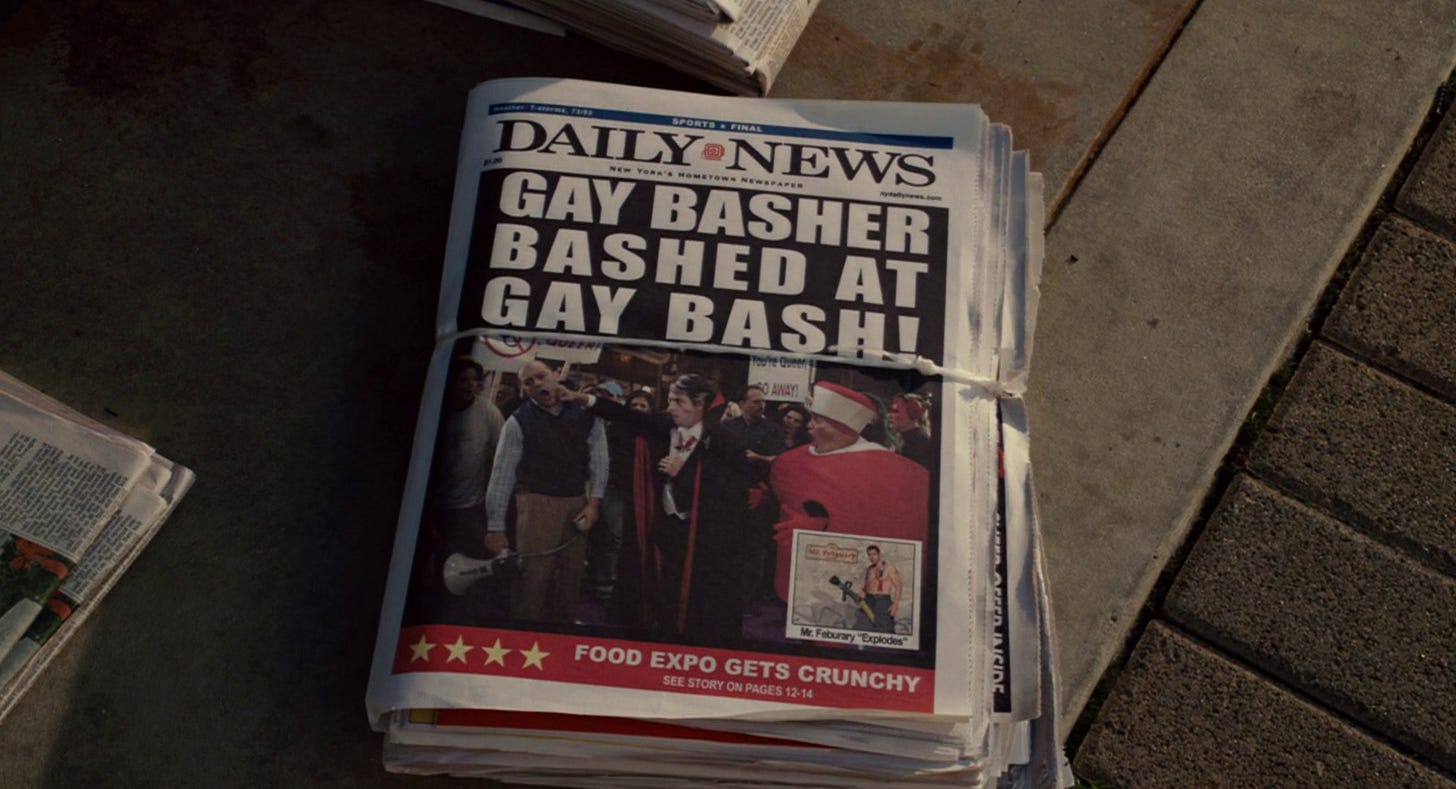

Economics: Just like Zodihogs weekend the masterpiece got absolutely bodied at the box office by a big broad “no homo” comedy, this time the number one opener I Now Pronounce You Chuck & Larry. Sunshine opened on July 20, 2007 on 10 screens at number 25 at the box office, just below Once, a fellow Fox Searchlight release in its 10th week of release playing on 112 screens. It would go on to make an embarrassing $7 million domestic. When coupled with its $28 million international box office and its $7 million in home video sales it barely broke even on its $40 million budget.

Boyle appears to be a real feast-or-famine director, with several of his other films also making basically break-even money (1997's A Life Less Ordinary, 2005's Millions, 2013's Trance, and 2015's Steve Jobs) or offering astonishingly huge returns on investment (1996's Trainspotting, 2003's 28 Days Later, 2010's 127 Hours, 2019's Yesterday, and of course 2008's Slumdog Millionaire for which I’m reasonably sure they needed to invent a new kind of dump truck to carry all the money that film made)

Other 2007 films visited this week:

Hairspray: As a John Waters fan I was 100% prepared to despise this film and was pleasantly surprised. Water’s subject matter is a little too coarse for your average Broadway show attendee, and while Hairspray is absolutely the most Broadway friendly Waters film, that’s a little bit like calling someone the valedictorian of summer school. While the musical definitely sands some of the edges off of Waters’ original it manages to still keep enough of them to render the story recognizable. The anti-racist story remains fully intact, but turns a little preachy and “inspiring” where the original film took more of a sardonic “look at these racist assholes” tone. Several casting choices are inspired (local teen dance show host Corny Collins is probably the part James Marsden was born to play, and Michelle Pfeiffer gives her all as villainous stage mom Velma Von Tussle, even though her existence in a film musical just caused my wife and I to think about her camp classic performance in Grease 2 the whole time), and I didn’t even mind the terrible fatsuit John Travolta was in that much (though both the flattening of the character of Edna Turnblad and his Baltimore accent are basically war crimes). ★★★★☆

I Now Pronounce You Chuck & Larry: It is a matter of record that I don’t care for “no homo” humor, so I was quite prepared to white knuckle my way through this Adam Sandler / Kevin James two hander that’s about a pair of firefighters who fake a marriage to have a life qualifying event to make some open enrollment changes in their pension. The entire film rests on the premise that “isn’t it HILARIOUS that these two macho dudes would need to fake being gay?” Here’s the thing: It’s not a great movie, but it’s not awful either. Sandler and James are skilled comedians and they’ve been given the resources to execute their vision. There are funny jokes and they are executed well. It’s just that for every two or three funny jokes there’s one that’s 1850s level offensive. Like, yes, Sandler’s character grows as a person and learns to stop saying the F slur but there’s multiple scenes featuring Rob Schneider as a stereotype of a Japanese man so broad that it would make Mickey Rooney in Breakfast at Tiffany’s blush. Also roughly half the conflicts in this film could be avoided if anyone had ever heard of a masc 4 masc couple. Still, it could have been a lot worse. ★★★☆☆

or third if you count Boyle’s 2000 adaptation of Garland’s novel The Beach. Garland didn’t write that screenplay though, and it features zero Cillian Murphy