In 1945, Akira Kurosawa directed The Men Who Tread on the Tiger's Tail. It’s not among Kurosawa’s better known films but it is important as his first film set during Japan’s middle ages, a setting that would become the director’s trademark across the next 40 years, including his masterpieces Rashomon (1950), Seven Samurai (1954), Throne of Blood (1957), The Hidden Fortress (1958) and Yojimbo (1961). Kurosawa is so successful at crafting these films that his name has become synonymous with “Samurai movie” for many moviegoers, despite the fact that he has made many excellent films with zero katanas.

No story takes place in a vacuum. Setting is crucially important. A storyteller can communicate volumes by relying on shared human narrative around where they set their story and who the characters are. A 12th century samurai carries a certain kind of weight and characterization completely different from a 20th century physicist. I could probably spend 500 words describing that difference, but why would I when “12th century samurai vs 20th century physicist” does the job for me? Beyond crafting a vibe and offering character shortcuts, though, a good setting will make a story feel lived in, and part of a broader world: a world that might contain someone like us, and it gives us a connection to that world.

In 1962, a young man named John Milius found himself on vacation in Hawaii during an unseasonable rainstorm that kept him from the beach. While looking for something to do, he found a movie theater that was playing a weeklong Kurosawa festival. Milius was so overwhelmed by what he saw that he not only fell in love with Kurosawa, but with the art of cinema in general, and decided to make it his life’s work. Upon returning home to California, he enrolled in USC’s School of Film & Television. There he met and befriended a classmate named George Lucas, who had only ever seen the down-the-middle mainstream American films that would play in his hometown of Modesto in California’s Central Valley. Milius introduced Lucas to Kurosawa’s films, insisting he come along anytime any of the director’s films were playing anywhere in LA, and Lucas fell in love with his distinct and striking visual style.

You may be wondering why I haven’t mentioned Pirates of the Caribbean: At World’s End at this point. I will, I promise. Not yet though.

George Lucas had long been a fan of fantastical fiction, reading books like The Skylark of Space by E. E. Smith, A Fighting Man of Mars by Edgar Rice Burroughs, and the Flash Gordon comic strip in his youth. Knowing as little about Medieval Japan as a young white man from Modesto would, Lucas found the experience of watching films like Seven Samurai and The Hidden Fortress akin to experiencing art about these faraway fantastical worlds, but unlike them, Japan is a real place, and its history is among the most well documented of human society.

Reading a short story by Isaac Asimov can feel more like solving a logic puzzle than like reading literature, as Asimov is constantly reminding his readers what the rules are of his sci-fi world. If he doesn’t, the point he’s trying to make about robots won’t make sense. If you’re watching The Hidden Fortress, though, you don’t need to know about the intricacies of the wars between the Yamana and Akizuki to enjoy the story. The Yamana and Akizuki are real Japanese clans, though, with their real iconography deployed in the film. One does not need to know that three nadeshiko flowers are the seal of the Akizuki clan, but it can both be inferred from context and be immediately understood by those who know the history and culture Kurosawa is referencing. The existence of those three flowers makes the world of The Hidden Fortress feel real in a way that I, Robot never really does.

You may be wondering if I’m ever going to talk about Pirates of the Caribbean: At World’s End. I promise I will

In 1977, George Lucas released Star Wars. You know this. Everyone knows this. It was and is a monumental piece of film. It was my parents’ first date. The amount of ink spilled about Star Wars’ successes could likely fill many barrels and I couldn't hope to sum them all up today. Today I don’t want to talk about the power of the Joseph Campbell monomyth, or the innovations in special effects, or the effortless charisma of Harrison Ford. I want to talk about lightsabers, Jabba the Hutt, and womp rats. The lesson Lucas learned from watching those Kurosawa films with John Milius 15 years prior was that using the setting of Medieval Japan made the films better, but also that one didn’t need to know anything about Medieval Japan to enjoy them. And so with Star Wars he made his own Medieval Japan.

At no point in Star Wars are we told what a lightsaber is. We are not told how they work. Obi Wan Kenobi simply says that it is “a more elegant weapon of a civilized age” as Luke Skywalker turns one on and tests its heft, and that is all we know. That’s all we need to know. It simply works as a cinematic device from that point on. Now if you’re a certain kind of nerd you know that a lightsaber operates with a kyber crystal powered by a diatium cell. The diatium creates plasma that is focussed through the kyber crystal like light through a prism that creates the concentrated “blade” out of the lightsaber’s handle. I know that because I’m a huge nerd. Maybe you knew that. George Lucas certainly knew it, but he didn’t tell us in Star Wars’ runtime. He simply used that internal logic of how a lightsaber worked to have his characters use them to create his own lived-in world. We aren’t told who Jabba the Hutt is in this movie, but we know that Han Solo owes him money. We don’t know the details of what the Clone Wars are, but we know that Obi Wan served in them. We don’t know what the Kessel Run is or what a Womp Rat is. We don’t need to. What we know is that George Lucas knows, and that makes the world of Star Wars bigger than the movie Star Wars.

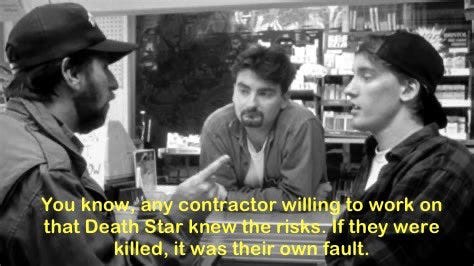

In 1994, the Kevin Smith indie comedy Clerks came out. As part of the indie boom of the early 90s, what Clerks lacked in production value was made up for by voluminous quantities of snappy and clever dialogue. Among the many snippets of banter throughout the film was a memorable scene when the film’s protagonist Dante and his bff / frenemy Randal discuss the morality of Luke Skywalker exploding the Death Star in Star Wars (1977). Implicit in the larger world that George Lucas had created was a small city’s worth of administrators, engineers, janitors, and contractors who would doubtless be staffing the genocidal planet-destroying weapon along with the evil Imperial military officers. Was Luke justified in killing these seemingly innocent non-combat imperial employees when he destroyed the Death Star? Or did these people understand the risks inherent of a posting anywhere in the Imperial armed forces?

I swear I’m going to get to Pirates of the Caribbean: At World’s End. I haven’t forgotten.

Kevin Smith did not portray Dante and Randal’s argument as being a pathetic bit of power-nerd navel gazing, but as a discussion of the implications of collateral damage in times of war using Star Wars as its framing device rather than an actual conflict. Talking about collateral damage in times of war could be incredibly emotionally charged if it were being discussed, as, say, part of the American-Vietnam conflict of 1955-1975. Discussing it in the context of Star Wars keeps the conversation light-hearted and comedic. As I mentioned in the 28 Weeks Later essay: a helpful thing about science fiction and fantasy is that it allows us to discuss the things that are uncomfortable to discuss in real life. Still, as much as I love that scene, and indeed as much as I love these kinds of discussions when I have them with my friends, I cannot help but think that this is a turning point in entertainment. Clerks wasn’t the first time two nerds have argued about Star Wars, but to the best of my knowledge, it is the first time that argument was meant to be understood as entertainment in and of itself.

Fans have been arguing about the minutiae of science fiction for virtually the entirety of the existence of science fiction. Ray Palmer and Walter Dennis created the "Science Correspondence Club" in 1930 as a means for sci-fi fans to connect and dork out over their favorite books, and that form of discussion has been going nonstop through letters to the editor to Amazing Stories and fanzines, in person in comic shops and at fan conventions, and of course from the earliest days of the internet, from BBS services to usenet groups to webforums to social media. The same arguments have been going for decades. What started to change at the turn of the century was that studio heads realized how much buying power these nerds had, and how much money they could put in their own pockets if they put this minutiae on the fringes onto the big screen.

And so this is what began happening. George Lucas took his notes for how the Old Republic and the Jedi Order had collapsed and turned them into three prequel films that would lead up to the events of Star Wars (1977). Critics hated them, as did many fans of the original Star Wars trilogy1, but they sure made money. Part of what drove these massive profits was the rise of nerd film bloggers, most notable among them being the behemoth Harry Knowles and his blog Ain’t It Cool News. Knowles and his network of production assistants, secretaries, and gaffers working on sci fi and fantasy properties would produce production stills and casting choices and snippets of screenplays that had not been made public. Knowles would write about them and post them on his site and drum up interest for these films from scraps of content. People did not see Star Wars Episode II: Attack of the Clones (2002) because they were excited about the story of Anakin Skywalker training to be a Jedi. They went to see it because they had been promised a cool droid that used lightsabers called General Grievous. They’d seen pictures on the internet and it looked radical. The lesson studios took could not be clearer. Storytelling was unimportant; what was important was the film looked and felt like an expansion of the lore established by the original property.

When you take a photo against an artificial background, it’s crucial that you don’t include the entirety of the background in the shot. Showing the entire thing only exposes its edges, and thus accentuates its artificiality. When what’s being demanded of the storyteller is “more of the world you’ve created, please,” it’s profoundly tempting to simply use the stuff that’s already been alluded to but not yet put into focus. The problem comes when you focus so much on the background that you lose the subject, and even worse, you might end up putting the edges in the frame and exposing how flimsy and silly it all is.

This is what Pirates of the Caribbean: At World’s End is. It’s two hours and forty-five minutes of procedural background on pirate lore as hinted at in the first two films and it fucking blows.

Rating: ★☆☆☆☆ It’s honestly rather incredible how quickly after the joyous surprise that the first Pirates of the Caribbean film was that the franchise lost its way and turned into a boring mess. A better use of your time would be to stare at the ocean and ponder your own mortality for three hours.

Economics: Pirates of the Caribbean: At World’s End opened 18 years ago today, May 25, 2007 at number one at the box office ahead of Shrek The Third. It would go on to make $309 million at the domestic box office. This would make it a commercial failure against its $300 million budget, but for the $650 million it made at the international box office, and the $300 million it would make in home video sales. To date there have been two additional Pirates of the Caribbean films and were plans for another to “complete” the series which were indefinitely put on hold due to Johnny Depp’s 2022 defamation trial against his ex-wife Amber Heard and the ensuing bad publicity generated by it. Bad filmmaking cannot kill a franchise like this, only celebrity intrigue and scandal can.

Other 2007 films celebrating their release anniversary

Bug: Michael Shannon and Ashley Judd star in this two-hander about a couple living in a motel in Oklahoma. What begins as a story about a pair of broken people with traumatic pasts who find each other and find a meaningful connection between them escalates into a terrifying shared delusion. Directed by cinema legend William Friedkin, Bug manages to be somehow simultaneously more terrifying than his masterpiece The Exorcist (1973) and more tense than Sorcerer (1977). The acting and filmmaking are top notch but boy howdy I have never been more stressed watching a movie than I was watching the final act of Bug. ★★★★☆

Including —according to the Clerks animated TV show— Randal from Clerks