Hamnet

A Film Diary Supplemental

While there is no plan for a unified project for this blog going forward, I like writing, and if you subscribe I bet it’s because you enjoy reading my writing, so if something strikes me as worth writing about you’re getting a piece on it. Last week I saw Hamnet, and it made me so goddamn mad that I had to write down some thoughts.

I have a pretty consistent set of responses that I get from movies. At best, they move me and let me step into another world for a couple hours and broaden my horizons. At worst, they bore me and make me wish that I’d spent a couple hours staring into the face of a loved one or out the window at a gentle summer rain instead. Few and far between is the film that actively makes me angry, and folks, Hamnet is one of those movies.

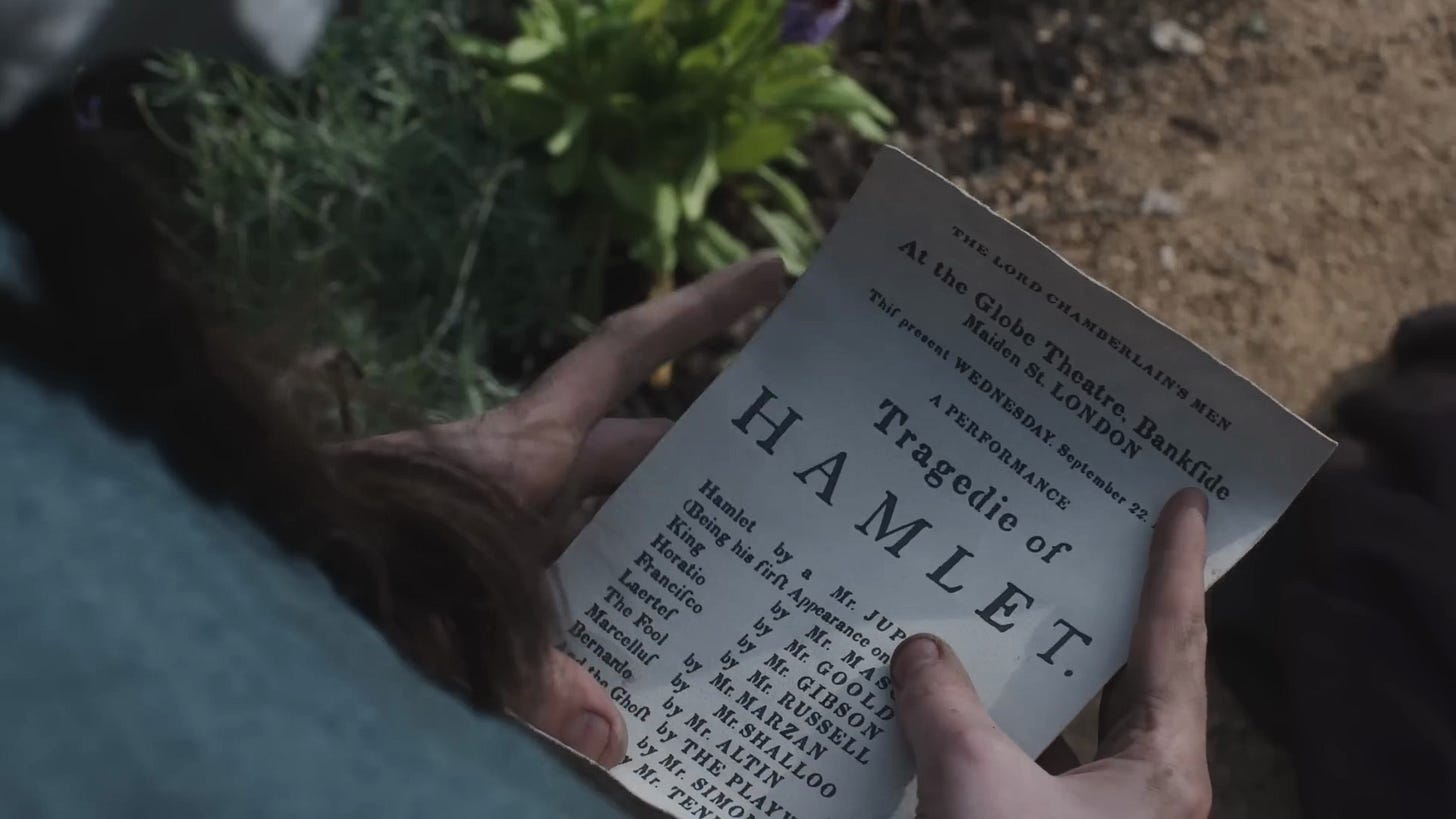

Hamnet is the story of Agnes1 Hathaway (Jessie Buckley), a woman who lives in the town of Stratford in England’s West Midlands. She spends her days foraging for herbs and hanging out with her hawk in the woods until one day she meets a local Latin tutor named Will Shakespeare (Paul Mescal) who catches her eye. They fall in love, get married, have children, and lead a generally happy life in Stratford but for the long stretches when Will leaves for London to work with a theatrical company. Their idyllic life is interrupted when their young twin children Judith (Olyvia Lynes) and Hamnet (Jacobi Jupe) fall ill with the plague, with Hamnet ultimately dying of the disease. Agnes blames Will for not being by their son’s side as he dies, and both parents fall into a deep depression afterwards. Will’s financial successes in the theater does nothing to lift Agnes’s spirits until one day she travels to London to see a new play that Will is putting on: The Tragedy of Hamlet.

Hamnet is a film that seems to have contempt for its own audience in a profound way. Ostensibly it’s for adults, but it also seems to have a preschooler’s understanding of human relationships, the work of William Shakespeare, and indeed the very concept of fiction. It condescends to the audience, seemingly thinking that without every plot beat having the subtlety of a sledgehammer that we might not get it. This bludgeoning of its themes and messaging renders every character flat and lifeless, not only disrespecting Shakespeare himself but also his wife and children that the film seemingly exists to elevate.

William Shakespeare famously left behind profoundly little in terms of correspondence or other papers that would give historians context for his work and details of his personal life, making the question of “accuracy” about historical fiction about his life moot. What little we do have is from historical vital statistics records: births, deaths, and marriages. We know that William Shakespeare wed a woman named either Anne or Agnes Hathaway on the 27th of November, 1582. We know that the couple had three children, Susannah, baptized 26 May, 15832, and twins Hamnet and Judith, baptized 2 February, 1585. We also know that Hamnet died young, and was buried on 11 August 1596, aged 11. We also know that one of Shakespeare’s best known plays is called Hamlet, raising the question “Is there a connection between Shakespeare’s dead son and his greatest work of tragedy?”

The author Maggie O’Farrell clearly thought so, as her novel Hamnet: A Novel of the Plague — the basis of Zhao’s film — is about exactly this. I have not read O’Farrell’s book, so I cannot speak to it directly, but I am given to understand its appeal comes not from extensively chronicled historical fiction but from the way its lyrical prose evokes a very specific sense of place about 16th century Stratford and a very specific sense of person in Agnes Shakespeare. Chloé Zhao is incredibly adept at evoking a similar sense of place and person in her visuals. The Stratford depicted on screen feels incredibly real and vivid and lived in, and the early scenes of Agnes wandering in the woods are positively intoxicating. I’d happily watch two hours of Agnes’s adventures with her hawk in the shade of the tall trees of the midlands forests. Unfortunately, the remainder of the film is attached to it.

The film first falls short in how it handles its dialogue. I know this is going to sound like some turbo-nerd “well actually” nitpicking, but I promise this film’s disservice to the language of Shakespeare actively renders the story worse. Shakespeare’s greatest strength is in not what his stories were but how he told them. His language is profoundly poetic and evocative to where it could conjure worlds beyond what the meager stagecraft of the 1590s could muster. Crucially though, he used language that was not flowery or inaccessible in its time. Normal everyday people flocked to Shakespeare’s theater, not merely the educated elite. If Shakespeare wrote for the screen in the 21st century, his comedies would have more in common with Nancy Meyer and The Farrelly Brothers than they would with Whit Stillman and Nicole Holofcener. When Shakespeare is performed well, it bears this out. As soon as your ears become accustomed to hearing “thou”s and “hath”s it simply becomes an engaging piece of theater. There’s a very good reason Baz Luhrmann’s Romeo + Juliet (1996) made three times its budget at the box office, and it’s not because The Cardigans were on the soundtrack.

The problem with Hamnet is that you need to get accustomed to those “thou”s and “hath”s for Shakespeare’s actual language to hit. The dialogue in Hamnet is very naturalistic to the present and anachronistic to its setting, which in any other circumstance I would not have a problem with. I don’t care about this kind of thing while watching Braveheart (1995) or The Favourite (2018). The problem I have is that when Susanna Shakespeare reads one of her father’s sonnets to her sister it doesn’t feel like it’s poetry written in the language she’s been speaking. It feels like homework. When the three children perform the introduction of the three witches from Macbeth, it doesn’t feel like children naturally play acting, it feels like homework. When Will is sitting on a London dock contemplating suicide and recites his own “To be or not to be” speech, it doesn’t feel like the earnest thoughts of a depressed man going through it. It feels like homework. Poorly performed Shakespeare always feels like homework, and if you’re going to go through the actions of creating these gorgeous sets and intricate costumes and painstakingly framing your shots to make Elizabethan Stratford feel real, why would you not do the same courtesy to the language of English’s greatest dramatist? I ask that question knowing the answer: because Hamnet doesn’t think its audience is intelligent enough to follow dialogue written in anything approaching the language of Shakespeare.

I could almost live with this, because in a big way Hamnet is not William Shakespeare’s story, it is Agnes Shakespeare’s story. I am no “great man of history” weirdo with a Roman statue avatar who bristles at the insinuation that a white man whose work is taught in high school is not at the center of everything. I don’t need Hamnet to celebrate Shakespeare. The fact that his work is omnipresent centuries after his death celebrates him. No, what turns Hamnet from irritating to straight up infuriating is the way it infantilizes Agnes Shakespeare, and with it all the women surrounding her.

At the center of Hamnet is a notion that Will and Agnes are deeply in love despite the fact that the society surrounding them thinks of them as weirdos. What Will sees in Agnes is undeniable. Despite the whispers in town about her that she’s a witch, Agnes is wise in the ways of nature, can see the future, is besties with a hawk, and looks like Jessie Buckley. That combination is catnip to a young, sensitive, overeducated young man, especially one with enough interest in fairy stories that he’s going to write A Midsummer Night’s Dream and The Tempest someday. What Agnes sees in Will is a little muddier. She asks him in the woods to tell her a story, and he obliges, telling the tale of Orpheus and Euridice. Very little actual Will Shakespeare poetry is on display in this scene, but that’s okay, he’s supposed to be young and nervous and hasn’t actually written Henry VIII yet. What we are meant to infer is that Agnes watches this shy young man open up like a flower and display his inner beauty. She sees who he is and loves him for it, which is what makes all that follows so irritating.

After finding him writing in the middle of the night, Agnes tells her brother Bartholomew that Will needs to go to London, saying that the smallness of Stratford will crush him. One would think that she knows that this is because she understands that he is a creative man, and to pursue his creative pursuits he needs to go somewhere where he will be appreciated, like London, where “the whole of the world gathers,” but at the same time, she does not seem to have a meaningful understanding of what exactly he does there.

After Will leaves for London and periodically comes back, Agnes begins to sense some distance growing between them. She regrets his absence as she goes into labor with her twin children without him. She refuses to come to London, believing Judith is too sickly to take to the city air, and ultimately she hates him for his decision to leave, screaming at him for not being there when Hamnet dies. She sees no value in it, only feeling his absence. After Hamnet dies, she says a line that appears in the trailer. I’d seen the trailer many times, and I had always taken it as Agnes encouraging her husband to lean into his artistic ways, but in context it comes across as sneering resentment:

That place in your head. You have gone to it and it is now more real to you than anywhere else.

I want to ask her “what do you think he’s doing in London? Why did you send him to the city if you think ‘that place in his head’ isn’t worth exploring?” Turns out, she apparently doesn’t understand what her husband even does.

Spoilers for Hamnet to follow

The emotional climax of the film takes place when Agnes goes to London upon learning that her husband’s new play is called “The Tragedie of Hamlet.” She first finds his apartment, a meager single room in a shared house. “Why would the man with the largest home in Stratford be living here?” she says. Big city rents, am I right? Will has been coming to London for years at this point. Do they never discuss his living arrangement? Not even as a matter of small talk? Do these two even engage with each other on any level? Apparently not, because immediately afterwards she goes to The Globe Theater to catch a performance of Hamlet where she is the worst audience member to have ever lived. As the play’s opening scene plays out where Horatio and the palace guards encounter the ghost of Hamlet’s father, Agnes asks her brother, “What are they saying? What has any of this to do with my boy?” Moments later when Horatio identifies the ghost as being the late king Hamlet, Agnes says, “his name! Why are they saying his name?” That’s right. Agnes Shakespeare is that boomer mom asking out loud “who is that guy?” when she goes to the movies once a year at Thanksgiving. It’s one (insulting) thing to say that Agnes is too much of a dum dum to follow the action of the play. It’s quite another for the wife of William Shakespeare to not seem to understand what a play is.

What kind of a relationship are we meant to believe that these two people have where she ostensibly falls for him because of his ability to tell stories, and then later on not seem to grasp that what he’s doing is telling stories professionally? It’s not like Hamlet was Shakespeare’s first play and she’s never seen Will write before. The idea that Shakespeare’s wife would have not even the beginning of an understanding of her husband’s work is to render her as an idiot. The payoff, then, is that the power of art is so great that even this idiot woman of the woods can be moved by it. I don’t think there’s any point where we’re meant to believe that Agnes is picking up on what’s going down on the stage. Again, because the film does not seem to want to engage with Shakespeare’s language in any way, the moments of Hamlet experienced onscreen just read as homework, so I don’t think that we — the audience of the film — are expected to pick up what’s going on onstage either] She is silenced by the presence of the actor playing Hamlet, but honestly it feels more like that’s because the actor is styled to look like a grown up version of her dead son3 than because she is meaningfully engaging with the play, as evidenced by the film’s final moment where Hamlet dies onstage.

As he acts out the poison coursing through his veins, the actor playing Hamlet stumbles towards the front of the stage where Agnes stands; she reaches out her hand to touch his (a normal thing to do for a person who has ever seen a play). Again, this is not her being so moved by the drama that she wishes to hold Prince Hamlet’s hand as he dies. This is her wanting to bid farewell to her dead son a second time. For some reason, the entire rest of the audience seems to understand Agnes’s gesture and also reaches towards the front of the stage (including people in the balcony seats way in the back who would have no chance of reaching the stage). The strings swell and it’s all very sad as the scene and the film concludes. The very final moment was so asinine I will not even describe it here. Feel free to read the film’s Wikipedia page if you’d like to know.

I am aware that there are plenty of people who have been moved by this film. Many of them were in the audience of my showing given how many sniffles I heard all around me. On some level, sure. The kid is dead and that’s tragic, and then she processes her grief and that’s triumphant. I don’t think that makes it good art. To say that “this made me cry and therefore it’s good art” is like saying that a gas station hamburger satisfied your hunger and therefore it was a good meal. It has fat and salt and protein and will keep you from being hungry, but it is not a good way to feed your body, and in the same way Hamnet’s heavy handed Lifetime-Original-level melodrama is not a good way to feed your soul. What makes me so profoundly mad isn’t just that Chloé Zhao appears to think that Agnes Shakepeare is this world class holy idiot, it’s that she appears to think her audience is, too, that the only way we’ll understand about how art can help us process our grief is by putting it in terms about as complex as fingerpainting. Do not let us marvel in the beauty of Shakespeare’s language, do not let us experience the power of Hamlet in a new light, just tell us that it’s sad when a kid dies but that it’s beautiful to remember the dead. Heaven forbid that a creator have faith in the intelligence of their characters or audience.

The “Agn” in Agnes is pronounced like the “Ang” in the name of the filmmaker Ang Lee, so it’s more “Ann-yes” than “Agg-ness”

those of us capable of doing math can surmise another biographical detail about Will and Agnes’s marriage

The actor who plays this actor is Noah Jupe, the older brother of Jacobi Jupe who plays Hamnet. Doubtless an intentional choice

Good god! This movie was wretched -- like Alex Garland's "Men" with a "he said the thing!" moment grafted on every ten minutes to wake you up -- and I thank you for being the only person with the stones to say as much. "How is Anne Hathaway -- who is 100% only called 'Agnes' because the cowards don't want you to think about 'The Princess Diaries' while watching this movie that is much worse than 'The Princess Diaries' -- not know what a play *is*?" was something I too thought.

That being said, I watched this at Alamo Drafthouse and thus could spend the large stretches of nothing in this film hunched over an order card and drawing a poster for a *better* movie named HamNet, about the first ever pig in the NBA, singlehandedly saving this from "worst movie of 2025" status for me, personally.