While talking on the NPR culture interview program “Bullseye” about his role as the title character in the Coens’ 2019 anthology western The Ballad of Buster Scruggs, Tim Blake-Nelson said that the trick to his performance was taking the ridiculous words, character, and setting of his homicidal singing cowboy segment and taking them deadly seriously.

[I] went to a drama school and studied Shakespeare and Shaw and restoration comedy. ... What that trains you to do, is to pick up a script… internalize the terms of its reality, and play them without any, um—without any sense of irony, or seeming over intentionality, or histrionics. You simply accept that that’s the truth. It’s a heightened world. And you become a part of it. And engage with it on its terms. You lift yourself up to its terms.

This technique was the secret behind the humor of every one of Preston Sturges’s films, from Eddie Bracken quaking with fear as he stutters the words “Ignatz Radskiwadski” to Joel McCrea being genuinely stunned at his own laughter while watching a Mickey Mouse cartoon. This was the secret of the humor of Raising Arizona, as Holly Hunter bursts into tears gazing upon her freshly stolen baby exclaiming “I love him so much!” This would later be the secret of the humor of The Big Lebowski as John Goodman muttered that he was “shomer fucking shabbos”, and the humor of Burn After Reading as Brad Pitt attempts to threateningly intone “we have… your shit”. It is indeed the secret to much of the humor of The Hudsucker Proxy, as Paul Newman gazes at his trousers and exclaims the word “Pants” in terror, as Jennifer Jason Leigh shouts crossword clues as she delivers exposition lines and types at a furious pace in the Argus newsroom. It is the secret behind how Hudsucker’s dozens of bit players deliver their one ridiculous line with utmost seriousness. There is one actor who does not deliver his lines with any seriousness, who treats every bit of dialog as a goof, constantly engaging with the world with irony, over-intentionality, and histrionics. It is the film’s lead: Tim Robbins.

The casting of Hudsucker’s lead was fraught. As a big-budget debut, the Coens were pressured to put a big name in the lead as their built-in draw would help to get butts in seats to make back its $25 million budget. Production company head Joel Silver after reading the script had one such name in mind: Tom Cruise. Tom Cruise, the tiny ball of charisma that he is, would have been the wrong choice. Norville Barnes must, at his core, be a bumpkin, and Tom Cruise is nobody’s bumpkin. Joel and Ethan Coen did not wish to cast Tom Cruise. If they had someone in mind, it is a mystery. Joel Silver insisted that Ethan Coen wished to play the role himself, but this statement must be taken with roughly a pillar of salt, as every statement he made about the film after it flopped dripped with bitterness. Silver also claimed that the Coens wished to cast 60s French New Wave ingenue Jeanne Moreau as Amy Archer despite the fact that she would have been 64 years old when principal photography began*. If Ethan Coen, an artsy Jewish writer living in New York who awkwardly interacted with Hollywood had the remotest bit of interest in stepping in front of the camera, surely the moment to do so would have been in Barton Fink, the low-budget arthouse film about an artsy Jewish writer awkwardly interacting with Hollywood, not the big-budget studio debut with everything to lose. How exactly Robbins was ultimately decided on has not been recorded, but it’s not hard to see how he was arrived at. In 1992 as the film went into principal photography, Robbins had freshly proven himself as being capable of holding a lead with an esteemed director, having just played Griffin Mill in Robert Altman’s The Player. He’d demonstrated his own sense of humor with his directorial debut, a political satire about a Republican folk singer named Bob Roberts. He was a star on the rise and clearly arty enough to work with the Coens and funny enough to carry a comedy. The one X factor was that there was always something dark and cynical about his roles, and Hudsucker was a light and airy departure from this.

In some ways, Robbins was the perfect choice. His tall, lanky physique, big broad grin and slightly awkward physicality fit the look of Norville Barnes to a T. In addition, Robbins is a skilled physical comedian, a necessary skill for a zany screwball comedy. Tom Cruise may be charismatic and have comic timing, but there’s no way he could have carried a scene in which he catches a wastebasket on fire, drenches the carpet with five gallons of water, sets his foot on fire, and catches Paul Newman by the pants. Robbins can convincingly lunge forward, squawk, spread his arms and launch into the Muncie High Fight Song. This however is not all there is to Norville Barnes.

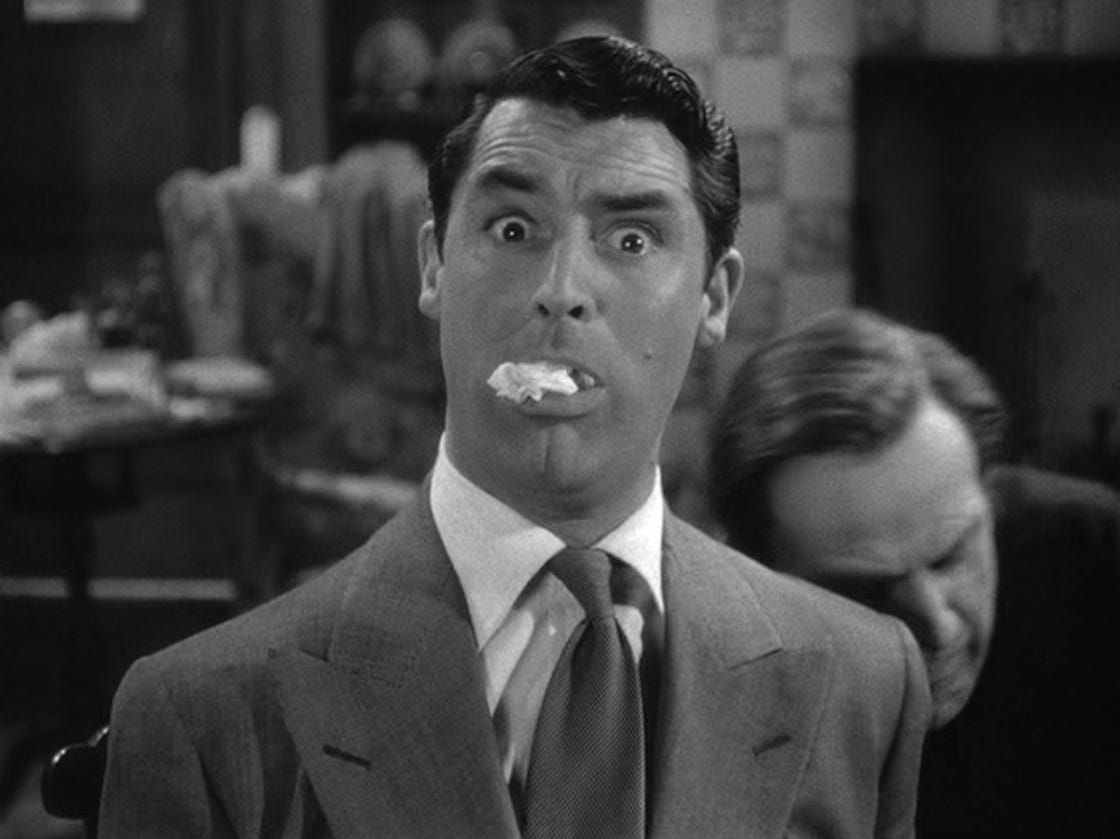

Robbin’s performance as Norville Barnes suffers when he opens his mouth. Specifically it suffers when he delivers a line designed to be funny. It’s not to say that he has no comedic timing and doesn’t understand what makes the lines funny, he absolutely does. His performance even has a clear antecedent in the world of studio-system screwball comedies. Robbins’s Norville Barnes seems modeled on Cary Grant’s performance in the 1944 Frank Capra film Arsenic and Old Lace. Arsenic and Old Lace is funny, but it’s humor comes from its cartoonishness. Everything in it is exaggerated to the point of being a grotesque. It’s hilarious, but Cary Grant’s twisting of his features into an exaggerated “whaaaaaaaaa?” at every plot reveal is a different kind of humor than what is being attempted in Hudsucker. Every actor who successfully delivers a laugh line in Hudsucker delivers it with commitment to the reality of the script. The problem with Robbins’s performance that he delivers the line with an implicit wink and a nod. He mugs in a way that implies “you and I both know this is idiotic, but I’m just playing along to be funny”. He never commits. He doesn’t deliver laugh lines as though they were deadly serious, and ironically that undercuts their comedy.

Thus Robbins —without meaning to— undercuts his performance constantly. As he presents his circle to Sidney Musburger, he affects a strange pose as he delivers his “you know, for kids!” catchphrase, signaling to the audience “yes, I know this is incredibly silly. Behold how silly I am as an actor in this silly movie”.

The same thing happens later in the same scene as he announces that he made dean’s list at the Muncie College of Business Administration. “This is a ridiculous sounding place” his physicality exudes. “No one serious could possibly come from a place called the Muncie College of Business Administration”. It happens time and time again in Robbins’s line deliveries. “You and I both know she’s just a dried up bitter old maid” he says, practically goofily winking at the audience that he knows he’s delivering this line directly to the woman he thinks he’s gossiping about. Possibly the most intense example of this phenomenon is as Amy is chewing him out for his selfish behavior as he is at the height of believing his own hype. Amy’s quick wit briefly fails her as she stumbles over a metaphor, accusing Norville of “chasing after money and ease and the respect of a board that wouldn’t give you the time of day if you… if you…”. Norville fills in with “worked in a watch factory”, causing a goon in his office to start laughing. Norville laughs along, but Robbins’s delivery of that laugh is nothing but a massive mug. “Look at how stupid that stupid joke I just said was”, his expression reads.

Robbins’s performance of Barnes is an attempt to have his cake and eat it too. He both wants to play a naive rube but also make us as the audience understand it’s all a performance, and he’s sophisticated enough to understand, like us, that Norville is a naive rube. In so doing, he undercuts his own believability. For Norville to truly work as a character, he needs to believe his own pitch. When Norville pitches “little something [he’s] been working on for the last two or three years” and produces his drawing of a circle, he needs to express “I am moments away from being plucked from obscurity into the life of a high powered executive I’ve always dreamed of”. When Norville says “I made dean’s list at the Muncie College of Business Administration”, he needs to say this in the same tone of voice as someone might say that they graduated top of their class at Harvard Law. When he finishes Amy’s sentence with his watch factory joke, he needs to laugh as hard as Joel McCrea did in Sullivan’s Travels as he watched that Mickey Mouse cartoon. Norville Barnes needs to buy his own hype to make his character work, and if Hudsucker has a fatal weakness, it’s that Tim Robbins does not convey that buy in.

None of this however is to say that Tim Robbins was incapable of doing a good job. Tim Robbins is an incredibly talented actor, and when he needs to, he has delivered this exact kind of comedic performance. His bit as Ian, the greasy-haired Baxter from High Fidelity (2000), was exactly this kind of performance, genuinely selling the audience on his sincere belief that he and the protagonist Rob could work their differences out with a quiet, well reasoned chat as Rob is on the verge of smashing his teeth out with a telephone, for example. I genuinely think that Robbins’s mugging was his genuine take on what would be funniest in Hudsucker, and had it been a different kind of Capra pastiche, it quite possibly could have been. The onus on correcting this was on Joel & Ethan Coen, men who by all accounts are loath to give any acting direction on set whatsoever. Paul Newman —a man who desired in every role he played to understand the character inside and out— said that the one piece of direction he got from the Coens was “try it faster”. The Coens modus operandi is not to actively direct their actors (or indeed their behind-the-camera collaborators as well) once production is rolling. It is to pick the right people and let them do what they do. This is no doubt why they keep working with the same actors, the same cinematographers, the same composer, the same storyboard artist. Their entire supervisory philosophy could be summed up as “They know what they’re doing. We’ll let them do what they do”, and if they don’t like it, they’ll simply not invite them back. Tim Robbins has been in one and only one Coen brothers feature. Had Joel & Ethan nudged him in a different direction, he very well may have been in more.

It’s easy enough for an idiot like me to play Monday morning quarterback** and say “Tim Robbins was the wrong choice”, but that is the attitude of a moron with a hot take. I am not a moron with a hot take. I am a moron with two hot takes.

Next week: who should have played Norville Barnes.

* This is not to say that it’s impossible to have a 64 year old woman as the romantic lead of a film. However to have a 64 year old French woman in an English-language role as the romantic lead of a pastiche of studio-system comedies where the leading lady was rarely on the wrong side of 30 that’s intended as a big budget large audience breakthrough seems like a stretch even for Joel and Ethan Coen.

** If the Monday morning in question is 26 years after the game was played.

"to have a 64 year old French woman in an English-language role as the romantic lead of a pastiche of studio-system comedies where the leading lady was rarely on the wrong side of 30" would make that "dried up bitter old maid" line land a lot differently as well