23: The Secret Romantic History of Amy Archer

Amy Archer first lets her Amy-Smith-from-Muncie mask slip at the Hudsucker Fancy Dress Gala when she tells Norville about her new years plans

There's a place I go now, the cutest little place near my apartment in Greenwich Village. It's a beatnik bar. You can get carrot juice or Italian coffee, and the people there — well, none of them quite fit in. You'd love it — why don't you come there with me — they're having a marathon poetry reading on New Year's Eve. I go every year.

How would Amy Smith, fresh off the Muncie express bus be able to go to a beatnik bar every year if she’s brand new in town? Of course this isn’t a trait of Amy Smith, it’s a reality for journalist Amy Archer. We eventually see the beatnik bar in question bookending the film’s Deus Ex Machina as it’s the last place Norville leaves before falling 44 floors and the first place he goes after he doesn’t quite squish himself. The establishment is as promised a beatnik bar, staffed by a bartender played by Steve Buscemi doing his best Maynard G. Krebs impression.

It’s clearly modeled after the real life beat hangouts of Greenwich Village of the 1950s such as The Café Wha? and The Gaslight as well as more notably 60s beat hangouts The Bitter End and Café Au Go Go. Beyond their locations in Greenwich Village establishing similarities to Amy’s beatnik bar, all of these establishments notably didn’t serve alcohol, not so much because they didn’t want alcohol to be consumed on site as much as they wanted to be free from the city’s liquor board and laws governing when bars could and could not be open, allowing for much more lax management and longer operating hours. Amy’s beatnik bar is likewise located in a basement, much like the Gaslight, whose heating and cooling ducts were connected to its upstairs apartments. While the folk music, poetry readings, and comedy performances weren’t loud enough to reverberate to its upstairs neighbors, the patrons’ loud applause was, causing its neighbors to call the police on them for noise complaints until the Gaslight’s management devised a solution: to show appreciation patrons were encouraged not to clap their hands, but snap their fingers.

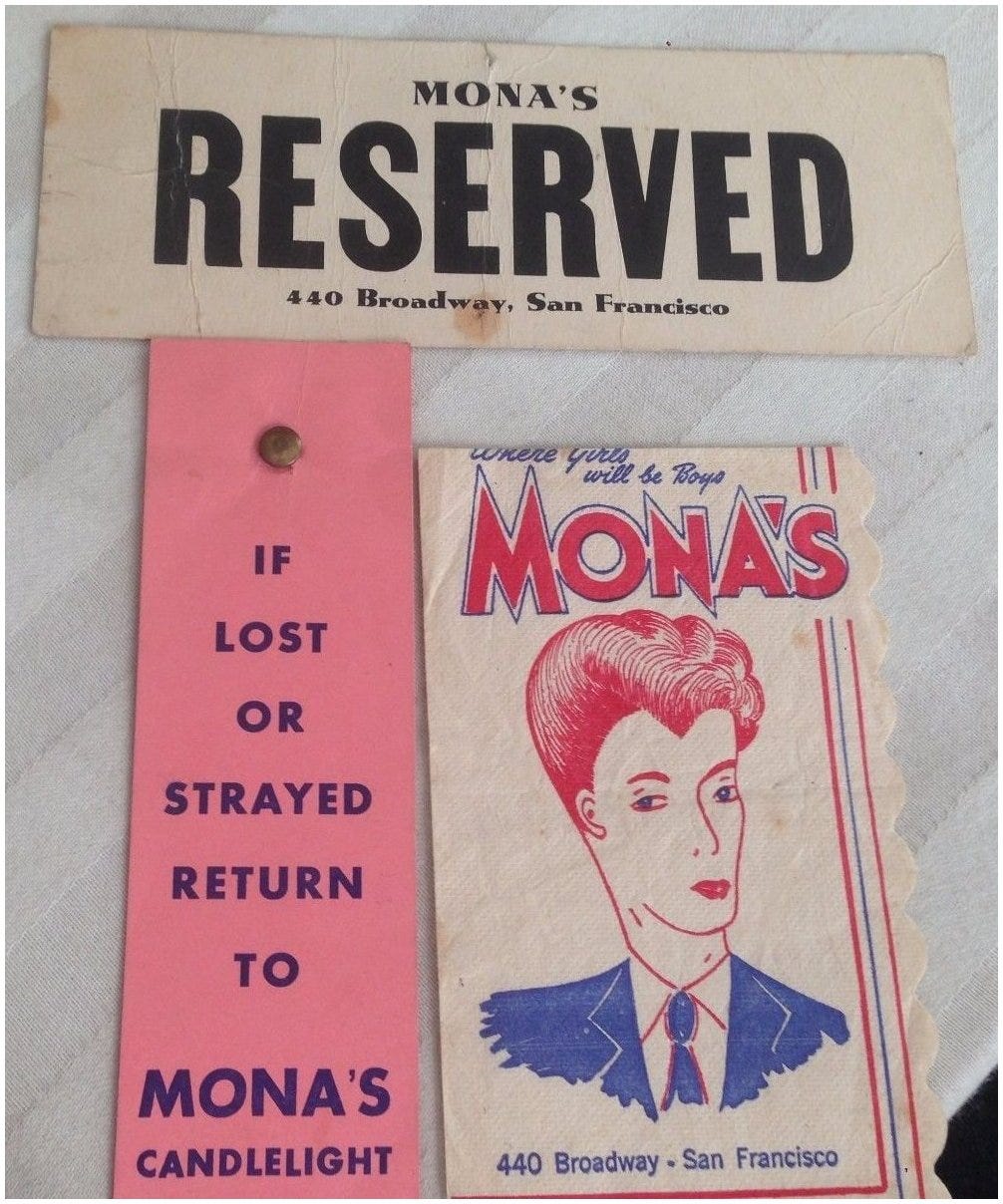

For it’s name however, the Coens interestingly didn’t choose something innocuously similar to these real beat bars, calling it something like The Cafe Who or the Lamplighter Cafe, they called it Ann’s 440. There was no beat bar called anything like Ann’s 440 in New York, there was however a notable bar in San Francisco that eventually became known as Ann’s 440. It was originally known as Mona’s 440, and its legacy is not as a beat bar, but as the oldest lesbian bar in the nation’s history.

Mona’s began life as simply “the 440” opening at 440 Broadway in San Francisco’s downtown North Beach neighborhood in 1936, but its owner Charlie Murray quickly brought in Mona Sargent as a co-owner, who had previously run a tavern called Mona’s around the corner. Sargent put her name on the sign, becoming Mona’s 440, advertising it as “Where Girls Will Be Boys” and having her all-female waitstaff and bar staff wear tuxedos.

Mona’s was also a live music venue and nightclub, booking primarily women entertainers who likewise were in on the club’s gender bending schtick, showcasing vaudeville revues and jazz and blues performers, most notably Gladys Bentley “The Brown Bomber of Sophisticated Song.” The club became popular not only among local women who loved women but also attracting a lesbian tourist crowd in its heydey in the 1940s and early 50’s, including many an armed servicewomen passing through San Francisco during WW2 and the Korean War. The decor and vibe and manner of dress suggest that it was a much more formal and much more lively venue than the sedate Gaslight or Café Wha? that Hudsucker’s Ann’s 440 is aping.

The club was purchased by Ann Dee in the mid 1950s who rechristened it Ann’s 440. Dee relaxed the women-focussed aspect of the club, allowing men such as a young Johnny Mathis to perform there, but she kept the club’s overall aesthetic and gay friendly atmosphere*, and most importantly kept the wait and barstaff, at this point almost entirely lesbian. While Dee didn’t promote and push the bar’s lesbian aspect as much as Mona Sargent had, the clientele was largely already established and was happy to continue coming to the same venue. The only relationship that Ann’s 440 could possibly claim to the beatnik bars of New York City is that a young and then unknown New York comedian named Lenny Bruce performed there after primarily performing at the Gaslight back home in Manhattan.

It’s entirely possible that Joel & Ethan Coen and Sam Raimi asked themselves while writing the film “what should we call our beatnik bar?”** and simply found the first place they could that Lenny Bruce had performed and left it at that. It’s curious though that they used the name of a real venue but specifically not a real beat venue, especially as the Café Wha? was still open, and a pair of Minnesotan-turned-New-Yorker Bob Dylan fans very much should have heard of the Gaslight Café. Why name your beatnik bar after a lesbian bar your female lead frequents if not to slyly say something about that character?’

The text contains next to nothing about Amy’s romantic life outside of smooching Norville a few times, however there is one line that’s intriguing. After the tabloids have implied that Norville and high fashion model Za Za are an item, Amy storms into Norville’s office and delivers an angry speech to him, at one point stating “I’ve never been dumped by a fella before and that hurts.” Amy’s age is never given. In the script she is simply described as “attractive, smartly dressed.” Jennifer Jason Leigh was 33 when the movie was filmed, and according to production company manager Joel Silver, the Coens’ first choice for the part was Jeanne Moreau*** who would have been 65 during production. No matter what, Amy Archer is not a fresh-out-of-journalism-school intern, she’s a veteran reporter at the Argus. While she is absolutely stunning, even the prettiest among us have been dumped, and typically before our early 30s. The devil could be in the details, and it’s specifically that Amy has never been dumped by a fella before. Maybe she’s been dumped by a girlfriend before? She bristles at being called “one of the guys” by Norville and is sensitive about her “mannish” mode of dress. These are valid bits of sensitivity in and of themselves, but they become even more poignant if she’s acting not only defensive about her mode of dress, but about her perceived taboo sexuality.

Amy Archer, queer icon?

The Coens are masters of the unnecessary character quirk, little somethings that don’t necessarily drive the plot further but absolutely do make their characters a little more charming. Llewelyn Moss in No Country For Old Men (2007) is defensive about the difference between welding and brazing. George Clooney’s Miles Massey in Intolerable Cruelty (2003) is obsessed with his teeth and the same actor’s Ulysses Everett McGill in O Brother, Where Art Thou? (2000) is obsessed with his hair. Peter Stormare expresses interest in Pancakes in two Coens films, first insisting “we going to pancakes house” as the laconic cold blooded killer Gaear Grimsrud in Fargo (1996) and then ordering “das lingonberry pancakes” (while his companion orders “das pigs in blankets”) as nihilist porn star / musician / extortion artist Uli Kunkel in The Big Lebowski (1998). It is ultimately of little import as to whether or not Amy Archer could be read as being a little queer to the overall story of the film, but it could be a delightful little easter egg. Writing a well rounded bisexual character is not necessarily a Coens move, but popping it in as a barely perceptible character quirk? That is a very Coens move.

*case in point, Dee took a chance on a young gay performer named Johnny Mathis and gave him his start.

**while Amy doesn’t mention the bar by name in the film, she does in the shooting script, so the name is definitely intentional and planned, not a decision made during production.

*** most of Silver’s thoughts on the film should be taken with a pillar of salt. He had taken a large financial risk in hiring the Coens for their first big-budget feature and the film turned out to be a flop. He has not worked with them since, and most of his comments on the film come from after the film had already flopped. It’s much more likely that they had expressed a desire for the actor who played Amy to be a Jeanne Moreau type. The type they were likely going for was Moreau’s work in the French New Wave such as The Lovers (1958) and Jules et Jim (1962), when she was 30 to 34.