03: Pants

In a letter to a friend where he was offering advice on how to write out plots, Anton Chekhov wrote “Remove everything that has no relevance to the story. If you say in the first chapter that there is a rifle hanging on the wall, in the second or third chapter it absolutely must go off. If it's not going to be fired, it shouldn't be hanging there.” It is the earliest recorded notion of the artistic notion of “Chekhov’s Gun”. The gun must go off; the setup must have a punchline; the pledge must be followed by the turn which is followed by the prestige. When we learn that Daenerys Targaryen owns dragon eggs we know that before too long there will be dragons. When Ripley shows she can use a robotic exoskeleton we know she’s going to use one to kill an Alien. When Brad Wesley’s goon is just driving around with a monster truck, you know it’s going to crush a car dealership before Dalton leaves town.

Joel and Ethan Coen are not beholden to Anton Chekhov or his gun. The Coens believe in the idea of events and plots existing in a film solely to be enjoyed on their own merits. Nothing exemplifies this more than the scene near the beginning of Hudsucker pertaining to Sidney Mussburger’s pants.

After having met Norville Barnes in a disastrous turn of events that sees Sidney lose his trash can, a window, and several pages of an important corporate document known as “The Bumstead Contract”, he has nearly lost his life diving for a page of the contract out his newly broken window. He is rescued by falling to his death by Norville who yells “I’ve got you Mr. Mussburger! I’ve got you by the pants!”. This causes Mussburger to look Norville in the eyes with a look of terror* and exclaim “Pants?” as he is transported back to the tailor’s shop where the pants were ordered.

As he is being fitted, the tailor (named “Luigi” in the shooting script though we never hear his name in the film) informs Musburger that he is going to give his pants an extra strong double stitch, which Musburger refuses as he feels it an extravagant expense.

Remembering this, we go back to the present, as Musburger observes his pants ripping at the waistband, right where that double stitch would be.

mn!” he exclaims, until we’re taken back to Luigi’s tailor shop after Musburger has left, and he announces to no one in particular “What the heck. Meester Moosaburger such a nice-a guy, I give him dooble steech-a anyway. Assa some-a strong-a steech-a, you bet!”** We flash back to the present, as Musburger’s pants stop ripping. The day has been saved by an act of inexplicable generosity that happened in the past, and we are whisked away to the next scene.

The question of Sidney Musburger’s pants are never again revisited. A different filmmaker who included this scene in act 1 might make Musburger’s extra strong double stitched pants his ironic downfall, say by getting his pants stuck to a railroad track in act 3. A different filmmaker might make Luigi’s inexplicable generosity*** a selling point of a later scene. Outside of a brief moment in the montage of the next scene, we never see him again. The argument might be made that it establishes a character trait: that Sidney Musburger is a cruel miser. Yet this is a character trait that has already been established not 15 minutes prior as Musburger begins plotting how he personally can profit from Waring Hudsucker’s death as Hudsucker’s cigar continues to smolder in the ashtray. The setup has no punchline. Joel and Ethan Coen have uttered the phrase “so this penguin walks into a bar” and then continued on with whatever thought they had before. The penguin just is in the bar. Sidney Musburger just has undeservedly strong pants.

An argument could be made that the scene exists in itself as simply a suspenseful scene. After all, Musburger’s life is literally in Norville’s hands at that moment, yet if the scene is intended to be suspenseful, it fails in that. There is a marvelous quotation from Alfred Hitchcock — the unqualified master of film suspense — about how to create suspense that I will quote in full:

There is a distinct difference between "suspense" and "surprise," and yet many pictures continually confuse the two. I'll explain what I mean.

We are now having a very innocent little chat. Let's suppose that there is a bomb underneath this table between us. Nothing happens, and then all of a sudden, "Boom!" There is an explosion. The public is surprised, but prior to this surprise, it has seen an absolutely ordinary scene, of no special consequence. Now, let us take a suspense situation. The bomb is underneath the table and the public knows it, probably because they have seen the anarchist place it there. The public is aware the bomb is going to explode at one o'clock and there is a clock in the decor. The public can see that it is a quarter to one. In these conditions, the same innocuous conversation becomes fascinating because the public is participating in the scene. The audience is longing to warn the characters on the screen: "You shouldn't be talking about such trivial matters. There is a bomb beneath you and it is about to explode!"

In the first case we have given the public fifteen seconds of surprise at the moment of the explosion. In the second we have provided them with fifteen minutes of suspense.”

The entirety of the pants scene lasts one minute and ten seconds. There are 26 seconds between when we first hear that Musburger has refused a double stitch and when his pants stop ripping. There are 19 seconds between when we first hear that Musburger has refused the double stitch and when we find out that he actually has been given a double stitch by his overly generous tailor. The amount of meaningful time spent in suspense over the state of Sidney Musburger’s pants is shorter than the amount of time the US Food and Drug Administration recommends that restaurant employees wash their hands for. Hitchcock’s suspense is defined in part by its lengths of time: Rather than spend 15 seconds on an explosion, we should spend 15 minutes worrying about an explosion. The 19 seconds we worry that Sidney Musburger’s pants are potentially in danger of ripping is not enough to build any meaningful amount of dread or anxiety. We have barely begun to think “oh no!” by the time we realize we have nothing to worry about. If the pants scene is intended as a moment of Hitchcockian suspense, it fails at it.

What I find to be both why The Hudsucker Proxy is both overlooked and why it deserves closer scrutiny is the fact that it attempts to pack 10 pounds of movie in a 5 pound bag. Every scene is overflowing with gags, references and clever shots. An argument could be made that if the scene had been given time to breathe and build suspense it could have worked on that level, but if every scene had been given room to breathe the film would have been three and a half hours long, but I cannot find this argument plausible given the rest of the Coens’ work.

The Coen Brothers are not Michael Bay, prone to blink-and-you’ll-miss-it edits and over-the-top short attention span scenes. It’s not even that they learned the restraint seen in later films such as The Man Who Wasn’t There (2001) and No Country For Old Men (2007) by doing such a quick paced and madcap movie as The Hudsucker Proxy. Blood Simple (1984) lives up to its name in that its plot is simple and moves slowly to create the exact kind of Hitchcockian suspense alluded to above. Even Raising Arizona (1987) lets its own absurd over the top humor breathe by letting the camera linger on H.I. McDunnough for five minutes as he runs down the highway with a stocking on his head carrying a bulk package of Huggies diapers.

I refuse to believe that the Pants Scene of The Hudsucker Proxy is a mistake. It simply is. It is turn without prestige. It is setup without punchline. A hillbilly walks into a music shop and that’s it. That’s all you get. It’s time to move on.

*It is possible that I am projecting here. Sidney Musburger as a character seems tailor made to never actually express emotion. His facial expression objectively barely changes, yet he is so expertly portrayed by Paul Newman that I can’t imagine his slightly flared nostrils and eyes opening one extra millimeter were not purposeful choices as to how this emotionless man portrays terror.

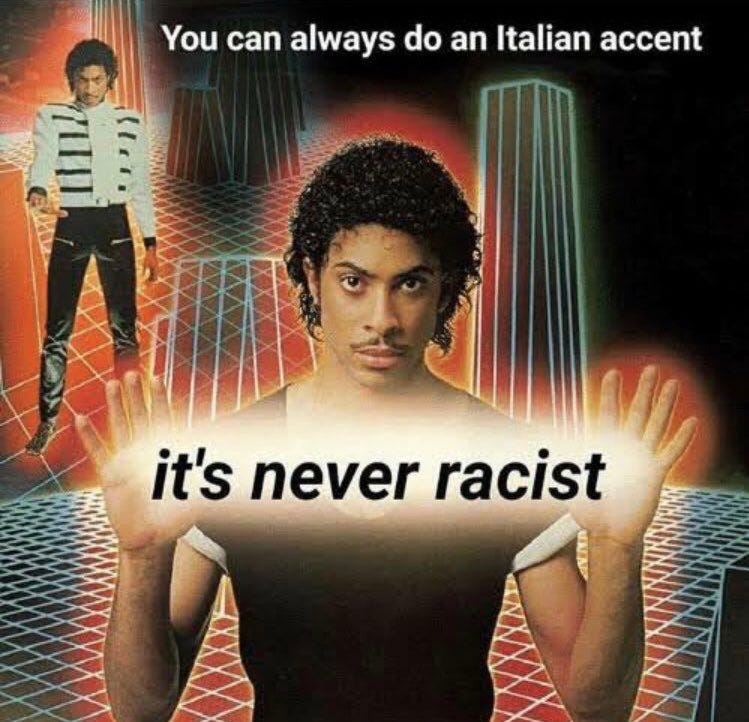

** In case anyone wishes to accuse me of anti-Italian racism, please note that first, I am copying the dialogue as it appears in Hudsucker’s shooting script and second:

*** The only interaction we see between Musburger and Luigi consists of Mussburger accusing Luigi’s dedication to quality work as being an attempt to swindle Musburger out of some extra cash. This accusation is delivered to Luigi’s face. This, and indeed the rest of his actions in the film clearly demonstrate that Sidney Musburger is not in fact “such a nice-a guy” and does not deserve the free double stitch he has been given.